The Trade Ties That Bind: Can the U.S. Economy Break Free from the Continent?

February 5, 2020

Getting it in writing can fail, especially as it pertains to mineral rights in for- eign subsoil. On March 18, 1938 Mexican President Lázaro Cárdenas signed an order that expropriated the assets of foreign oil companies operating in Mexico. This was followed by the founding of Petróleos Mexicanos (PEMEX), a state-owned firm that became the monopoly operator in a country that in the 1920s rose to be the world’s second-largest oil producer. As for who got the boot, the Mexican Eagle Company was a British subsidiary of the Royal Dutch/Shell Company which accounted for 60% of Mexican oil production. American-owned firms including Jersey Standard and Standard Oil Compa- ny of California, now Chevron, made up roughly 30% of total production. Be- cause the bulk of oil was exported, so were the associated profits, a situation worsened in the Great Depression when demand crashed producing a glut in global oil supplies. Further fanning the flames, the oil giants paid Mexican workers half as much as other employees working in the same capacity.

The labor unrest culminated in the 1937 oil strike and ultimate nationalization of Mexico’s oil industry. Retaliation came in the form of an oil embargo which halved Mexican oil exports and pushed the country to become the primary supplier of Nazi Germany. While Britain was able to sever its diplomatic ties, Mexico’s close proximity gave the United States no such luxury. Upon the outbreak of World War II, the U.S. pressured American oil firms to settle. On April 18, 1942, the U.S. and Mexican governments signed the Cooke-Zeveda agreement which paid out roughly

$29 million in compensation. Holding out until 1947, the Brits eventually recovered $130 million. By 1950, attempts at reconciling commercial ties had failed sending

U.S. operators into the friendlier domiciles of the Middle East and Venezuela.

As for Mexico’s acquiescence, the combination of America’s ascent to superpower status and the advent of the Second World War forced the issue. Trade with Europe was slowly displaced by the growing appetite of its northern neighbor and Mexico was and is a democracy. Within two days of the attack on Pearl Harbor, Mexico cut ties with Germany and Italy. The sinking of two Mexican oil tankers by German U-boats in the Gulf of Mexico was the last straw. On June 1, 1942, President Manuel Ávila Camacho issued a formal declaration of war against the Axis Powers. U.S. Secretary of State Cordell Hull hailed the moment as, “evidence that the free nations of the world will never submit to the heel of Axis aggression.”

Mexican soldiers would go on to fight valiantly as did those of Canada, America’s neighbor to the north. Since that bygone era, much has changed in relations be- tween the three nations, especially as it pertains to roles played in the global energy industry. The relatively recent rise of Canadian and U.S. production stands in stark contrast to the 40-year decline in Mexico’s production.

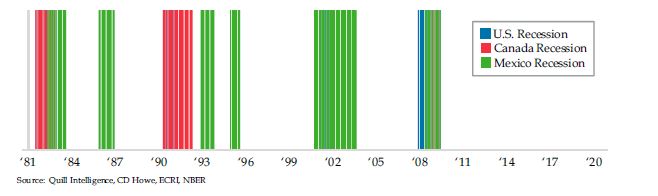

Regardless of the source of commerce, there is an undeniably tight symbiosis between the economies of the three countries. With Mexico in technical recession and Canada’s economy slowing significantly, it’s fair to ask whether the U.S. expansion can continue even if both of its neighbors are in recession. Given such a feat has never been possible in the past, then is it different this time?

The United States Has Never Avoided Recession When Both Canada and Mexico Succumb to Contraction

The biggest risks posed to the three countries taken together are two of the biggest sources of collective growth – energy and autos. As detailed recently in The Shale Evolution (click title to link to that Weekly Quill), the United States has risen from producing 5% of the world’s oil in 2008 to nearly a fifth today. Saudi Arabia and Russia have both been dethroned and the U.S. now dominates global production. As has become the norm, any run-up in oil prices is greeted by shale players turning ‘on’ the spigot on pre-fracked wells. The short-lived Iranian spectacle was no exception. The minute West Texas Intermediate crossed the $60-threshold, U.S. production rose. In the last week, a fresh record high of 13 million barrels per day (bpd) was hit.

Comparable figures on Canada show daily production nearing 6 million bpd plac- ing Canada 4th in the world in terms of production. The explosion in production accompanied Canada’s oil sands boom which began in 1998. Back then, Canadian production was all of 2.2 million barrels a day. The oil sands account for two-thirds of Canadian output and are expected to drive a doubling in Canadian production by 2050. Technological advances, including fracking, are also expected to contribute to the increase and bring down costs materially.

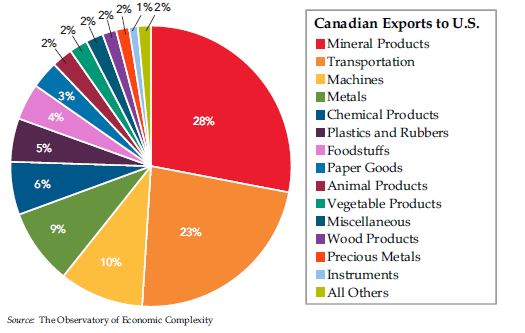

No surprise, Mineral Products account for 28% of Canada’s exports to the U.S. Trans- portation comes in a close second but is responsible for Canada being the biggest export market for the U.S. There is a veritable hum of rail activity on the Canadian border linking Detroit and its northernmost operations.

Canadian Exports Dominated by Energy and Transportation

As of November 2019, Chi- na remained the largest source of U.S. imports. But fed by the ongoing trade war we’re supposed to pretend has been partially resolved, Mexico comes in a close second and is America’s top trading partner when total trade figures are tallied. But you have to squint to see the 3.9% of Mexican exports tied to Mineral Products. Since its creation, Pemex has segued from being a source of national pride to one of shame. The executives themselves will tell you it’s a bloated, egregiously inefficient and corrupt organization. Last October, Pemex extracted 1.6 million bpd, matching the level of production last recorded in 1979.

As of November 2019, Chi- na remained the largest source of U.S. imports. But fed by the ongoing trade war we’re supposed to pretend has been partially resolved, Mexico comes in a close second and is America’s top trading partner when total trade figures are tallied. But you have to squint to see the 3.9% of Mexican exports tied to Mineral Products. Since its creation, Pemex has segued from being a source of national pride to one of shame. The executives themselves will tell you it’s a bloated, egregiously inefficient and corrupt organization. Last October, Pemex extracted 1.6 million bpd, matching the level of production last recorded in 1979.

The difference between then and now is that the 1.6 million total gave the country bragging rights. That same number today represents abject failure. To place the figure in context, the discovery of the Cantarell mega-fields at the end of the 1970s propelled production to a peak of 3.4 million bpd in 2003. The global financial crisis proved too much for the company that had been milked for its cash flows but mismanaged to distress. Since 2009, Pemex’s annual expenses have exceeded its income. This turning point forced the firm to incur growing debts. In inflation-adjusted terms, Pemex’s financial obligations have swelled 113%, from $32.5 billion to about $103 billion over the past decade.

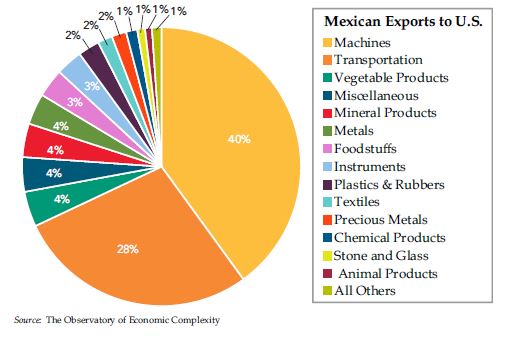

The saving grace for Mexico’s economy has been its industrial sector. Machine exports ac- count for 40% of Mexican exports to the U.S. while Transportation contributes 28% to the total.

Mexico’s Export Economy Driven by Industrial Sector

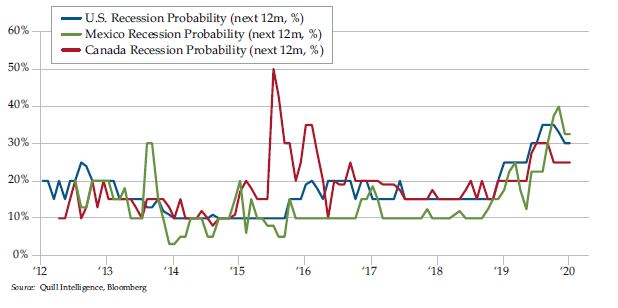

As for what the future holds for these trading partners that are tied at the border, it would be amus- ing if it wasn’t somewhat distressing that recession probability models only put about a third odds on Mexico being in recession while it’s in recession. The next closest economy to recession is Canada when viewed in hard data terms. You may note its recession probabilities are even low- er than those of the U.S.

As for what the future holds for these trading partners that are tied at the border, it would be amus- ing if it wasn’t somewhat distressing that recession probability models only put about a third odds on Mexico being in recession while it’s in recession. The next closest economy to recession is Canada when viewed in hard data terms. You may note its recession probabilities are even low- er than those of the U.S.

Why waste your time and occupy space on this page with this graph? It is beneficial to see how gravely the collapse in oil prices affected Canada. On a fundamental level, however, as an investor, it’s critical to fade the media’s obsession with declining recession probabilities. Recall the construct of these models – they are a simple comparison of short-maturity to long-maturity yields. And don’t fool yourself. We live in a world in which the biggest central bank forcibly un-inverted the yield curve by buying the very T-bills whose yields had surpassed those of longer-dated Treasuries. And the rest of the world’s sovereign bonds trade off U.S. rates. It’s not bearish or bullish. It is what it is and nothing more.

Recession Probability Models Defy Reality

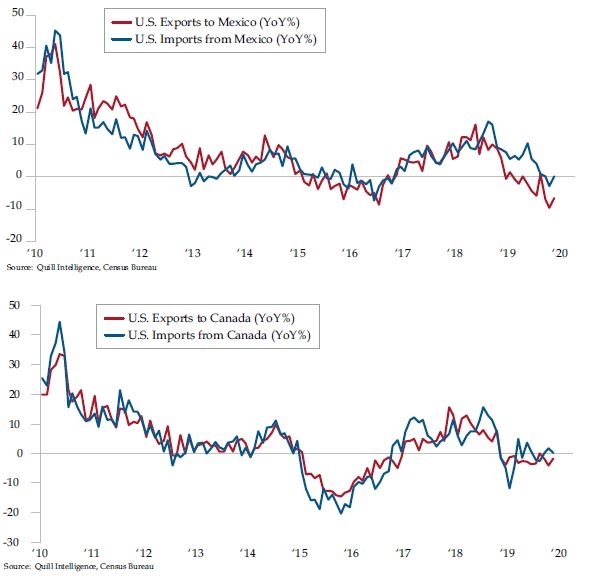

You are better served by following the hard data flows between the countries, an undertak- ing that will involve more charts and fewer words from this point on. As you can see, trade between the U.S. and both border countries has bounced off its recent lows as the worst of the trade war seems to have passed. The concentration of Mexico’s industrial sector vis- à-vis Canada has made it that much more painful economically. That said, the continued anemia increasingly plaguing the shale patch in the U.S. has materially raised the risk that Canada falls into recession.

Zooming out, the de-globalization story we read about is evident in the lower level of trade dynamism that’s occurred over the course of the last 10 years.

Trade War Casualties

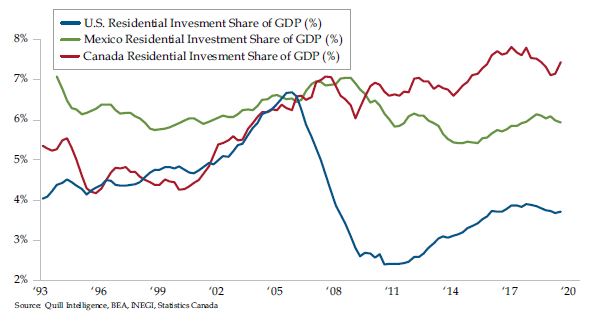

While relatively low oil prices have been a drag of late, it’s housing that poses the greatest danger to Canada’s economy. Even at the apex of the housing bubble, residential real estate did not begin to contribute as much to U.S. GDP as has been the case in Canada in recent years. By the looks of Canadian housing activity, the global recession that slammed the U.S. never occurred north of the border. Over the past year, though, housing has begun to stumble. China clamping down on yuan flight has arguably hit Vancouver harder than any city in the world. An unprecedented level of immigration has gone a long way towards backstopping the market.

Even so, housing starts slipped under 200,000 in December and are down by -8.1% over the prior 12 months. This is the third consecutive negative print. There’s a nontrivial prob- ability Canada slipped into recession in the fourth quarter. We already know given the availability of monthly data that the economy contracted in October.

Rosenberg Research and QI friend David Rosenberg who calls Toronto home made the case that the downshift in housing, “is a clear-cut negative for an already-overvalued Canadian dollar and augurs for a renewed shift to an easier Bank of Canada stance. Whether we see rate cuts or not, the markets will continue to price them in and likely force the Bank’s hand. All in all, the Canadian economy is stagnant at best and disinfla- tionary pressures are going to build in this backdrop. That’s good news for rates across the curve.”

A Tale of Three Housing Markets

The less well broadcast story is that of Mexico’s housing market. Years ago, when I worked at the Dallas Federal Reserve, staff papers were written about the advent of a mortgage market in Mexico. What advanced economies have long since taken for granted is a rela- tively new phenomenon that has catalyzed a housing boom that has also been a greater con- tributor to GDP than has been the case in the U.S. save the very top of the housing bubble in 2005. As you can see, this source of support for the Mexican economy is well off its peak.

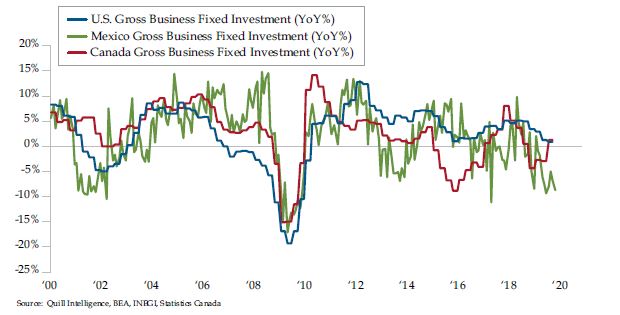

Stepping back, the three economies’ long-term prospects are vastly different. Purely in eco- nomic terms, the drug war that continues to ravage Mexico has met its match in President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador. While there are multiple forces at work, investment in the country has plummeted since he took office in December 2018. The contraction in invest- ment has reached the lows seen during the 2015/2016 industrial recession and threatens to sink to levels not seen since the U.S. Great Recession.

In 2013, the Mexican Constitution was amended to allow for private investment in oil and gas. Starved for capital and technology though it is, three months prior to taking office, Lopez Obrador announced he would suspend auctioning off any new oil blocks for at least two years. He has also pulled funding to modernize much of Mexico’s infrastructure in lieu of increased social spending. The likely beneficiary of this last move is Vietnam. As multinationals sought to build fresh supply chains due to the protracted trade war, Lopez Obrador’s hostile overtures to foreign investors turned U.S. companies away from choosing Mexico as a destination. The potential GDP left on the table is immeasurable. As an aside, the sickening slide in U.S. investment is as damning a picture as can be painted, testament to the Fed’s gross misjudgement.

Long Term Economic Prosperity Hinges on Stable Investment

Despite being buffeted by the decline in oil prices and the industrial recession, thanks to residential real estate, the Canadian economy has been relatively resilient. Absent a reversal in flows from China, this shield looks to be giving way. The implications are dire given the example of the United States when its household sector took a similar blow 12 years ago. And that was with a peak of debt-to-disposable income of 130%.

That same metric in Canada is 176% today as households have had to take on record levels of debt to afford home prices that have experienced runaway growth chased as they were by foreign buyers who were immune to sticker shock. As low as interest rates are, households devote 15-cents of every dollar of disposable income to princi- pal and interest payments on debt.

Businesses for their part see the writing on the wall. Three separate gauges of Canadi- an business sentiment have been trending downwards in recent months. As is the case with all economies, things won’t get truly hairy until jobs are lost. And while Canada did manage to outrun expectations in December, with job gains of 32,500 compared to an expected 25,000, the trend is less than inspiring.

As per Rosenberg, “Don’t be fooled because employment growth has virtually come to a standstill over the past three months and the goods producing sector is in clear contraction mode over this period. Not just that, but in the past three months, full-time jobs in Canada have declined 16,100 even with the December recovery.”

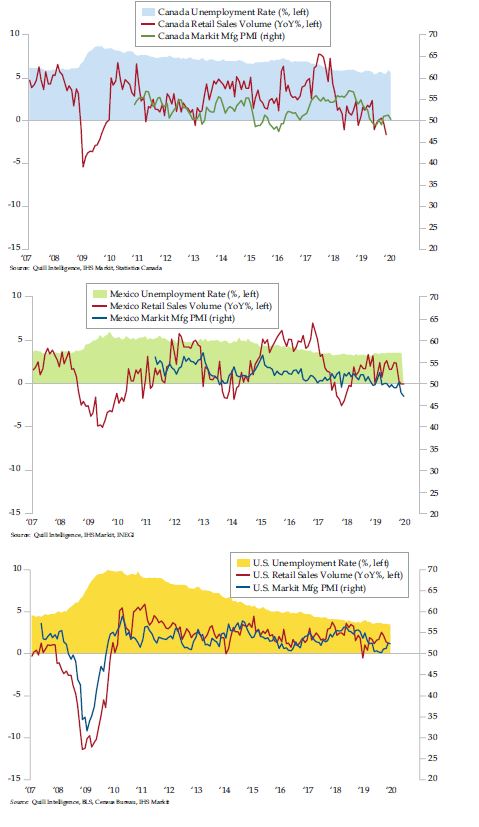

Wage growth has also slowed to a 3.8% rate over the past year compared to 4.4% in October. Hours worked has also fallen to 0.3% over the prior 12 months, down from 1.8% in mid-2019. Both of these suggest investors fade the message in the decline in the unemployment rate to 5.6% from 5.9% given what appears to be in the cards in coming months. Of course, the unemployment rate is one of the last economic indicators to turn in any cycle. For the moment, all appears to be rosy on that front in the case of all three countries as you can see.

North American Labor Market Resilient

Unlike the United States, the soft survey data on the manufacturing sector has yet to re- bound in Canada and Mexico, at least as gauged by Markit data given the U.S. ISM remains in contraction. One could argue that the U.S. will lead the other two economies, which is perfectly plausible. That said, it’s odd to see retail sales fall into contraction in both countries and maintain that this should be a harbinger of a turnaround in the industrial sector. It puts the cart before the horse given household spending is typically not hit until after the factory sector turns.

While Mexico’s recession has been shallow – the economy contracted by 0.1% in the three quarters through the third quarter when growth “improved” enough to flatline – GDP slipped back into the red in October and by 0.5%, the steepest since last March. More recent data suggest the economy re-entered recession in the fourth quarter.

The country lost 382,210 jobs in December taking job creation for all of 2018 to 342,000, half of 2018’s showing. December is typically the worst month for Mexico’s job market as employers fire workers to avoid paying a holiday bonus and then re-hire them in the new year. Be that as it may, the magnitude of December job losses suggests something bigger is pulling down the economy.

Squaring that circle requires data from the auto sector. In 2019, Mexico’s auto production declined by 4.1%, the second consecutive annual decline and the biggest since the recession Mexico suffered in 2009 after the financial crisis. Even worse, Mexican auto exports slipped by 3.4%, the first annual decline since 2009. Add to this the fact that auto exports to the U.S. rose by nearly 11% in the 11 months through November. As we’ve written for some time, fleet sales in the U.S. have cushioned four years of declining retail car sales.

The global and secular auto industry decline was fully apparent in declining Mexican ex- ports to Canada, which fell by 12.5%, Europe with a 20.1% decline and worst of all, Latin America where shipments sank by 28.6%.

AMIA, Mexico’s auto trade organization, is forecasting another year of contraction for the industry, which will likely be exacerbated given the December capitulation in U.S. fleet car sales. At a recent news conference, departing AMIA president Eduardo Solis remarked that, “It’s not a matter of the plants’ capacity, it’s about how much of this production the market is absorbing. We’re seeing major falls at a global level.”

How likely is it that the Mexico economic contraction deepens without affecting economic activity to its north? The last Mexican economic recession that was not accompanied by a U.S. slowdown took place in the 1990s during the Tequila Crisis, a collapse in the Mexican peso sparked by a violent uprising in Southern Mexico and the assassination of a presiden- tial candidate in 1994.

Look no further than President Lopez Obrador, again, for a separate strain pressuring the economy. Banco de Mexico board members place the blame at one of the president’s first moves after he took office, raising the minimum wage by 16%. This month, he pushed through an additional 20% boost, seven times the rate of inflation.

Mexico’s central bank lowered its key interest rate in each of its past four meetings and by one percentage point in total in 2019. The current rate of 7.25% is hoped to boost the stagnant econ- omy as inflation slowed to its 3% goal. But minutes from Banxico’s December meeting showed concern that this next step up in mandated wages will feed through to a rise in inflation.

The aim is not to castigate Lopez Obrador as a person. His goals of fighting poverty and inequality are noble indeed, and necessary. One of the reasons the progressive was elected in the first place was the populace’s rebuke of his predecessors who kept a lid on wages to make exporters to the S. more competitive on the global stage.

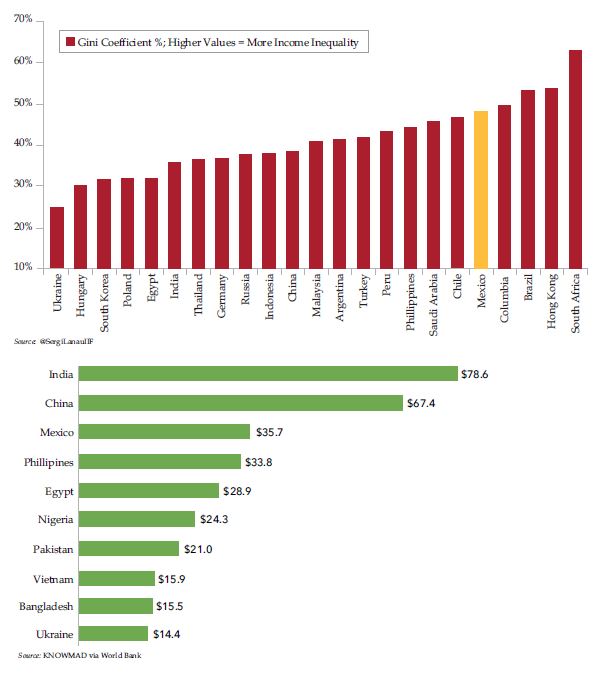

A glance at the following chart illustrates how grave the inequality crisis is in Mexico. Only Columbia, Brazil, Hong Kong and South Africa have higher levels of inequality. The incen- tive to flee the country for better work in the United States is plain. Though immigration has fallen off in recent years, Mexico remains the third most reliant country on remittances from expats to buttress its economy as you see in the second panel.

Inequality Has Driven Mexican Outmigration

As mentioned, Canada has experienced an unprecedented surge in immigration in recent years. CIC is a Canadian newsletter focused on immigration. The outlet recently published the following forecast: “Canada looks poised to welcome roughly 3.5 million permanent residents over the coming decade — by far the highest intake in the country’s history. It would mark a 25% increase compared with some 2.8 million permanent residents it admit- ted over the last decade.”

Programs designed with the intent to increase immigration have spurred the influx of fresh settlers. The government is keenly aware of its aging population, which only grows by 1% per year. The natural birth rate accounts for 20% of annual population growth while immigration is credited with the other 80%. Within 10 years, the natural rate of growth is expected to fall to zero meaning all population growth will be tied to immigration.

While migration from Mexico only accounts for 2% of Canadian immigration, that still rep- resents an improvement since the passage of 1994’s North America Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). With any luck, the passage of NAFTA’s successor will ensure trade ties remain as strong as they are which benefits all three economies.

At the highest level, one would have to be naïve to suggest that the fate of the world’s largest economy depends on two industries that play significant roles in three economies. It is accurate, however, to say that much of the marginal growth in the U.S. economy in the current cycle has been attributable to autos and energy.

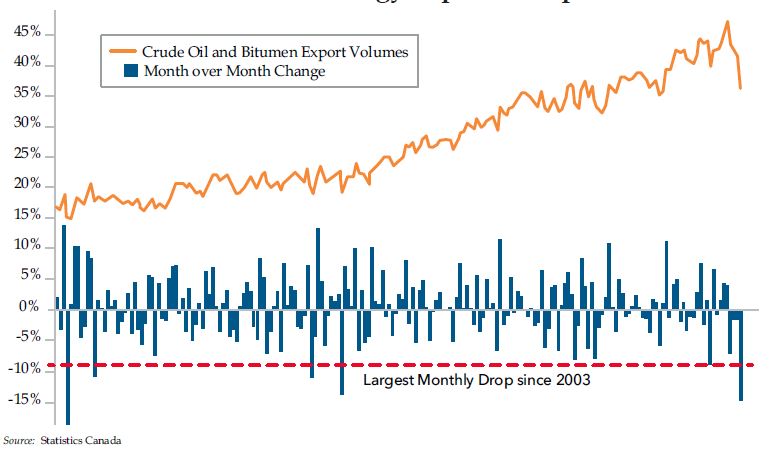

As is the case with so many economic issues, much comes down to whether a rebound is seen in the global economy. De-globalization may be intensifying as one nationalistic wave after another crashes onshore throughout the world. But that doesn’t imply that the inter- connectedness of the global economy is at risk of extinction. The slump in global demand for oil is largely at play in this last chart. As you can see, Canadian energy exports have just suffered their worst decline since 2003. This same pain is being felt in the state of Texas and throughout America’s energy-dependent states where jobless claims are rising at the fastest pace in the nation.

Canada Suffers Worst Energy Export Slump in 16 Years

As for autos, if fleet sales in the U.S. don’t bounce back, further production cuts are all but guaranteed. This will be a second body blow to both Canada’s and Mexico’s economies. The recession in Mexico will deepen and Canada will surely succumb to contraction. There is no such thing as writing on the wall until we see the U.S. consumer stumble.

It is possible that auto sales to U.S. households rebound. And that might be sufficient to prevent a recession in Canada which in turn, saves us from having to ask if the U.S. is truly impervious to recessions on both its northern and southern borders for the first time ever. If evidence does continue to mount that Canada is following Mexico into recession and the

U.S. and its mighty printing press manages to skirt the same fate, we would finally be able to pronounce that it really is different this time. And we know that happens every day.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.